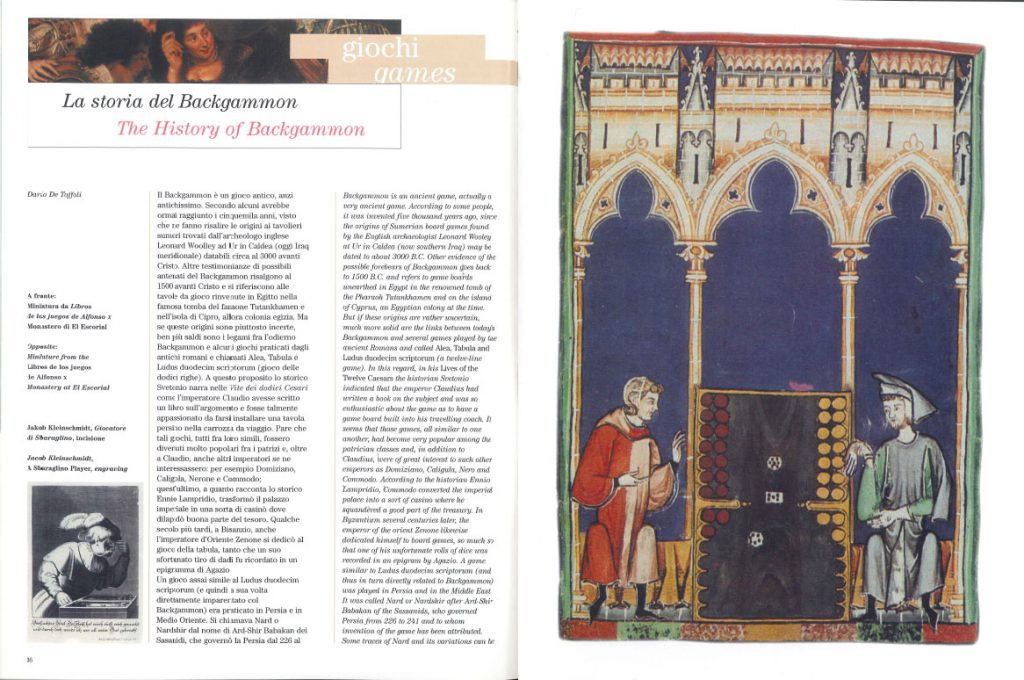

Giornalismo ludico, cioè scrivere “sui” giochi e sui più vari aspetti della cultura ludica. Informazioni, cronache, recensioni, storie di giochi e giocatori, risvolti matematici, aspetti sociali e filosofici.

ARTICOLI

Cultura ludica; matematica nei giochi; azzardo e azzardopatia; riflessioni sul gioco e sul giocare; archeologia e storia dei giochi; game design; giochi in TV, al cinema e in letteratura; storie di giochi e giocatori; recensioni; dentro le tecniche del gioco; informazioni e cronaca… questi e altri sono gli argomenti di cui trattiamo nei nostri scritti!

Alcuni esempi:

10 maggio 2017

Giugno 2014

Di 2048 si è scritto tanto: per esempio che Gabriele Cirulli, il giovane friulano che l’ha proposto open source, si è ispirato a prodotti già esistenti (cosa che del resto lui stesso ha dichiarato); poi che esisterebbero giochi simili strategicamente migliori, eccetera eccetera.

Per chi vuol sapere tutta la storia basta consultare Wikipedia.

Fatto sta che 2048 ha attecchito e milioni di persone l’hanno giocato e lo giocano.

E l’ho giocato anch’io, con una certa soddisfazione e pure una leggera vertigine di “addiction”.

Il gioco va per potenze di 2, nello schema compare ad ogni mossa un nuovo 2 (in posizione imprevedibile) e qualche volta un nuovo 4. Poi mano a mano che due numeri uguali si toccano, si fondono nella loro somma, cioè nella successiva potenza di 2. Due 2 diventano un 4 (22); due 4 diventano un 8 (23); due 8 diventano un 16 (24) e così via fino a raggiungere lo scopo del gioco, cioè 2048, che altro non è che 211.

Ma in realtà il 2048 l’ho raggiunto subito, fin dai primi tentativi e non mi era sembrato particolarmente difficile e quindi non mi aveva dato particolare soddisfazione. E così sono andato avanti, raggiungendo prima 4096 (212) e poi anche 8192 (213).

A questo punto sì che il gioco si faceva difficile: fino a dove si sarebbe potuti arrivare?

Però con numeri così alti nello schema subentrava un altro tipo di frustrazione, bastava un 2 che compariva nella casella sbagliata per scombinare tutto e vanificare magari un’ora di “lavoro”, o magari bastava anche un tocco impreciso nello screen perché l’iPhone mandasse tutti i numeri in una direzione diversa dalla voluta e, di nuovo, si rovinasse irreversibilmente la partita.

Dunque?

Come raggiungere i limiti teorici? E anzi, quali sono i limiti teorici?

Una prima risposta potrebbe essere 216 (vale a dire 65536), dato che le caselle sono proprio 16; anzi si potrebbe riempire tutto lo schema con le potenze crescenti di 2, cioè 2 nella prima casella, 4 nella seconda, poi via via 8, 16, 32… fino a 65536.

Praticamente impossibile.

Però poi ho trovato in internet una versione con la funzione “undo”, che permette cioè la cancellazione della mossa effettuata, se le conseguenze non sono quelle programmate, per esempio se il nuovo 2 compare in posizione sbagliata: semplicemente si cancella e si rifà la mossa. Di nuovo in posizione sbagliata? Si cancella ancora e si rifà.

Uhm… forse così sì che si potrebbe arrivare ai limiti teorici! Ma che lavoro lunghissimo!

E poi, a questo punto, non si potrebbero ancora espandere i limiti teorici? Eh sì, perché se nell’ultima casella compare un 4 anziché un 2 possiamo risalire tutte le 16 caselle fino ad arrivare a 217, nientepopodimeno che 131072! E magari poi riempire tutte le caselle partendo da 22 per arrivare fino, appunto, a 217.

La cosa mi ha ingolosito e l’impresa si è rivelata davvero impegnativa. Malgrado l’undo mi sono trovato a superare passaggi impegnativissimi… insomma una vera sfida, come piace a me. Ci ho messo più di un mese, con circa 150.000 tocchi di schermo (anche considerando 1 secondo a tocco sono 40 ore abbondanti). Ma alla fine ci sono riuscito, non so quanti altri pazzoidi come me abbiano scalato questa montagna, so che raggiunta la vetta, per un attimo, ho avuto un lieve senso di astinenza… e adesso?

Ecco comunque il print screen col risultato delle mie fatiche.

Vabbè dai, non internatemi in manicomio… prometto che non lo faccio più!

In realtà mentre giocavo non ho tenuto conto dello score, ma solo della configurazione finale, quindi – a parità di configurazione – sarebbero teoricamente possibili score leggermente superiori, assumendo che compaiano sempre 2 e mai 4 se non nelle poche volte (credo siano 16 in tutto) in cui il 4 è indispensabile per completare il gioco.

Una veloce ricerca in internet mi ha portato a trovare presunti “record del mondo” con punteggi inferiori al mio (che è stato di 3.885.680).

Dario De Toffoli

Demis Hassabis

Video intervista a Demis Hassabis, fondatore di Deep Mind, nonché padre del rivoluzionario algoritmo di AlphaZero.

Ragazzo prodigio negli scacchi, computer game designer, neuroscienziato, imprenditore di successo (la sua start up Deep Mind è stata venduta a Google per 625.000.000$), direttore di una delle più avanzate ricerche al mondo di intelligenza artificiale e soprattutto “world class all-round player” (il più forte multi-giocatore di tutti i tempi?) ed è naturalmente in quest’ultima veste che io lo conosco. Dal 1997, quando non aveva ancora 20 anni.

In questo mio articolo del 2016, racconto qualcosa di lui:

https://www.ilfattoquotidiano.it/2016/02/13/intelligenza-artificiale-uomo-battuto-anche-a-go-cambiera-il-mondo/2450156/

Nel video una chiacchierata (circa 25 min) in cui parliamo di giochi, dei suoi successi, del futuro delle Mind Sports Olympiad e anche delle sue ricerche, che nei prossimi anni potranno letteralmente cambiare il mondo. L’intervista è del 2015 e devo dire che lui sta mantenendo le sue promesse, il suo algoritmo ha avuto incredibili sviluppi sia nel campo dei giochi che in quello della medicina. https://deepmind.com

Ne riparleremo presto.

Intervista effettuata nel 2009

Gordan Markotich

Zagabria, Croazia

data di nascita: 11 aprile 1959

titolo: maestro internazionale

massimo rating ELO: 2455

GLI SCACCHI E LA VITA

Il maestro internazionale Gordan Markotich si racconta

Gordan, chi sei tu?

Ho cinquant’anni e nella vita ho fatto molte cose diverse, ma se mi chiedono di presentarmi sono molto orgoglioso di dire che sono un maestro internazionale di scacchi, perché in questo modo ottengo rispetto. Se invece dicessi che gioco a backgammon o a poker non sarebbe la stessa cosa, non me ne potrei certo vantare.

Dunque gli scacchi sono il gioco che gode del maggior riconoscimento sociale?

Quando giocavo da professionista in Francia, Spagna e anche Italia, ero piuttosto povero, ma godevo di buona considerazione, non contava com’ero vestito, godevo – come dici tu – di un importante riconoscimento sociale, cosa che oggi credo manchi.

Come hai cominciato con gli scacchi?

Ho imparato a giocare a 4 anni, mi ha insegnato mio padre. L’idea di passare al professionismo, di guadagnarmi da vivere con gli scacchi, l’ho avuta invece abbastanza tardi, a 25 anni. Ero sposato con prole e lavoravo come operaio, insomma ero abbastanza infelice. L’unica cosa che sapevo fare discretamente era giocare a scacchi, allora per risollevarmi mi sono messo a studiare. Poi sono diventato maestro internazionale a 29 anni.

Peccato che non tu non abbia studiato prima, forse saresti diventato un grande maestro?

Credo di sì, infatti è stata una mia grande sfortuna. Se posso, approfitterei per dare un consiglio tecnico ai giovani giocatori italiani.

Prego.

Il fatto è che in troppi hanno questa idea fissa dell’importanza del sorprendere l’avversario nella fase di apertura: ebbene è una cosa sbagliata… che anch’io facevo da giovane. È molto più importante studiare e praticare le aperture principali, normali: questo è fondamentale per giocare bene a scacchi.

Che atmosfera si respirava nella Zagabria dove sei cresciuto culturalmente? In termini scacchistici, naturalmente.

Io sono croato, vivevo in Jugoslavia e in quel periodo si giocava a scacchi ovunque, in ogni casa c’era almeno una scacchiera. Io avevo un po’ di talento, già da piccolo vincevo sempre e a 14 anni ero campione giovanile. Grazie a questo successo sono entrato nel più importante circolo di Zagabria, per me è stato come entrare in chiesa. C’erano tutti i più forti giocatori della zona ed è stato facile migliorare, perché ho avuto la possibilità di giocare con i grandi maestri. È stata un’esperienza incredibile. Si facevano un sacco di partite, ma mai completamente gratis, c’erano sempre in palio degli spiccioli, per avere lo stimolo a non mollare mai. Però purtroppo non si studiava molto, la teoria non era presa nella giusta considerazione, contava solamente la pratica… e mi rendo conto che si trattava di un errore enorme.

E la guerra, Gordan? In qualche modo gli scacchi ti hanno aiutato…

Questo è abbastanza interessante. Nel maggio del ‘92 mi sono ritrovato in guerra, al fronte. Ero soldato semplice e 24 ore di prima linea si alternavano a 48 ore in retroguardia, dove si aveva molto tempo libero. C’era qualcuno che giocava a scacchi, ma erano molto scarsi e non me ne sono interessato. Però un giorno ho visto due soldati che giocavano, uno dei quali continuava a vincere e a deridere l’avversario. Questa sua arroganza mi ha dato fastidio e quindi l’ho sfidato: lo vinsi facilmente anche se, per umiliarlo, gli avevo dato una Torre di vantaggio. Il “pubblico” iniziò a deridere il mio avversario, ma non si accorse di quanto fosse alto il mio livello di gioco, e così, per soddisfare il mio ego, decisi di dimostrare a tutti chi fossi; sfidai di nuovo il mio avversario dichiarando che avrei giocato “alla cieca”, senza guardare la scacchiera. Il pubblicò aumentò e assistette incredulo alla mia nuova facile vittoria. Per tutti diventai un genio… e non mi furono più assegnate mansioni pericolose. La verità è che per uno scacchista normale giocare alla cieca non è una cosa così difficile, ma ai non scacchisti appare spettacolarmente geniale.

Approfitto di questa bellissima storia che ci hai raccontato per farti una domanda, nei panni del “non scacchista” che considera il gioco alla cieca, se non geniale, almeno speciale. A tuo parere, quanto conta la memoria negli scacchi?

Secondo me non molto, io per esempio non credo di avere una grande memoria.

Scusa se ti interrompo, ma per quanto ne so, tu hai una memoria grandissima, ricordo che mi hai descritto mossa per mossa una partita di backgammon che io quasi non ricordavo di aver giocato con te…

Ho forse più una memoria selettiva nel campo degli scacchi, del poker e del backgammon, ma per le altre cose non ricordo nulla, devo sempre chiedere ai miei figli come si chiama questo attore, come si intitola quel film, un sacco di cose. Invece il più grande giocatore della mia epoca, Kasparov, ha una memoria fotografica eccezionale e l’ha anche dimostrato, ma lui è davvero un genio a cui nessuno si può paragonare.

Cambiamo discorso, come sbarca il lunario un maestro internazionale di scacchi?

Quando sono diventato professionista, la cosa più conveniente era giocare per le squadre, perché i circoli possono trovare sponsor più facilmente. Si possono ottenere ingaggi di tutto rispetto e quindi non ti sogneresti mai di “vendere” delle parttie. Mentre giocando partite individuali devi fare i tuoi conti a fine mese, sai il maestro internazionale non guadagna molto.

Vendere?

Sì, forse “vendere” è un termine troppo forte, comunque l’etica era questa. Nei tornei, soprattutto all’estero quando giochi per la patria, non ci si vende mai una partita… ma quando giocavo da solo era prassi normale. In un torneo col sistema svizzero, con 8 o 9 turni, è determinante soprattutto l’ultima partita, quella che decide se torni a casa con del denaro o meno. E a volte ci possono essere risultati che convengono ad entrambi i giocatori; il sistema svizzero è molto crudele e ti può portare a patteggiare con l’avversario. A questo proposito c’è anche un episodio interessante…

Vuoi raccontarcelo?

Giocavo nella Coppa Croata e all’ultimo turno era tutto ancora possibile, la mia squadra poteva ancora vincere, anche se non eravamo i favoriti. La notte prima della finale un giocatore della squadra avversaria venne da me e mi offrì una grossa cifra per perdere la partita. Colto alla sprovvista ho risposto che ci avrei pensato e naturalmente è stato un grosso errore, avrei dovuto dire subito di no, perché – come ho detto prima – la squadra non si vende mai. Sono subito tornato da lui rifiutando decisamente la sua proposta. Lui ha poi raddoppiato l’offerta e io non solo ho nuovamente rifiutato, ma sono andato dal presidente del mio circolo raccontando cosa fosse successo e dicendogli che l’indomani avrei preferito non giocare. Lui invece mi ha fatto giocare lo stesso, ma io non ho retto la situazione: ho giocato malissimo, ho perso la partita e tutti hanno pensato che l’avessi venduta. Il fatto è che un professionista, in qualsiasi disciplina, deve sempre essere pronto a qualsiasi tipo di pressione… e io in quel caso ho fallito.

Come mai hai abbandonato gli scacchi? È una cosa abbastanza insolita…

Vero, è assolutamente raro che un giocatore del mio livello abbandoni gli scacchi. Io giocavo solo all’estero per le squadre tedesche, francesi, spagnole, mi pagavano abbastanza bene e questo mi era sufficiente. Poi si sono aperte le frontiere e molti giocatori ex-sovietici, non solo russi, sono entrati in Europa occidentale. Una concorrenza spietata, giocatori duri e forti, abituati a condizioni pessime: lottavano in ogni partita come se fosse una questione di vita o di morte, giocavano meglio di me e chiedevano meno soldi. Non hanno avuto troppe difficoltà a prendere il mio posto in Germania. Per giocare a scacchi devi avere una grande passione, ma quando il gioco diventa una professione devi anche essere ben motivato e preparato mentalmente. Molti giocatori sono caduti, e in parte anch’io, per questioni legate alla vita di tutti i giorni: stabilità familiare, soldi, cose del genere.

Chiuso con gli scacchi, sei passato al backgammon: una scelta o un caso?

È stato proprio un caso. In Francia giocavo a scacchi per la squadra di Nizza, guadagnavo abbastanza bene, ma avevo bisogno di arrotondare: nel loro circolo l’unico gioco in cui si potesse guadagnare qualcosa era il backgammon. All’inizio non sapevo nemmeno cosa fosse, poi ho imparato meglio di altri ed ero anche molto fortunato… per farla breve, guadagnavo più soldi con il backgammon che con gli scacchi.

E ora col poker, il gioco che oggi va per la maggiore.

Mi sono messo a lavorare nel campo del poker, perché in realtà io non sono un giocatore, quasi preferisco lavorare. Nel mondo del poker mi sono trovato benissimo, vi sono entrato in una età molto tarda, ma ho fatto moltissimi miglioramenti. Poi sono anche diventato direttore di tutti i tornei al casinò di Campione e per me è stata una soddisfazione enorme. Ho anche giocato e vinto parecchio, ma pensandoci bene è un gioco che non mi piace, nel campo del poker preferisco lavorarci, troppa gente è caduta nella trappola del credere di poter guadagnare facilmente da professionista del poker.

E a scacchi, non giochi proprio più?

L’ultima volta ho giocato 5 anni fa. In realtà sono il primo scacchista croato in assoluto che è andato liberamente a giocare in Serbia, mi avevano invitato degli amici ad un torneo. Ne sono orgoglioso. Così è la vita, ero in prima linea proprio contro i serbi, ma poi sono stato il primo a giocare assieme a loro.

Per chiudere, hai un consiglio da regalare ai lettori?

Ho la sensazione che di scacchi potrei parlare all’infinito. Posso dare un consiglio ai genitori: se avete un figlio che tende un po’ a isolarsi, offritegli gli scacchi, aiutano molto. A me hanno aiutato tanto… se non fossero esistiti gli scacchi io non sarei diventato nessuno. Io ho un’enorme gratitudine verso questo bellissimo gioco!

Grazie Gordan, e tanti auguri per i tuoi futuri progetti!

Paco de la Banda

Già il nome ispira simpatia, ammettetelo.

Paco è un grande, ha vinto il Pentamind nel 2010, ha ufficialmente rappresentato la Spagna in innumerevoli giochi, è davvero fortissimo in tutti i classici (scacchi, go, bridge, dcc).

Era un affermato dirigente aziendale, poi un a decina d’anni fa l’illuminazione, proprio qui alle Mind Sports Olympiad: si dimette e comincia a insegnare giochi nelle scuole, ai bambini dai 6 ai 12 anni. Guadagna meno, ma è più felice.

E qui a Londra quest’anno ha tenuto un seminario sul rapporto fra i giochi e la vita, cioè come le decisioni che si imparano a prendere nei giochi di strategia possono aiutare a prendere le decisioni giuste anche nella vita.

Ankush Kahndelwal

È nato in India, è cresciuto in Inghilterra e l’ha rappresentata nelle squadre juniores sia di scacchi che di bridge.

È un matematico e ha lavorato come analista finanziario alla borsa valori… poi si è stufato e ora vive giocando professionalmente a poker e la sua specialità è l’Omaha head up online (scelta per alcuni moralmente discutibile, d’accordo, ma se lui ci può vivere perché è più bravo… certo non si tratta di un gioco d’azzardo).

Ogni anno migliora e batterlo sarà sempre più difficile.

Riccardo Gueci

Riccardo Gueci, ovvero gli scacchi in Sicilia. Ma non solo, anche il Mensa… e anche tanti tanti altri giochi, dal bridge all’othello a tutto quello che c’è di nuovo da imparare. Così mi piacciono gli scacchisti, aperti al resto del mondo e non chiusi in un guscio che loro si immaginano dorato. Da qualche anno condivide con me l’avventura delle Mind Sports Olympiad londinesi ed è divertente fare squadra.

Cosimo Cardellicchio

Studioso dei giochi di Alex Randolph, esperto di teoria dei Giochi, autore dell’importante “Giocatori non biologici in azione”, appassionato conferenziere (non correte il rischio di dargli un microfono in mano, perché lui non smetterà di parlare…), qui a Londra si cimenta solo in due specialità, l’amato Twixt e l’Osare (che poi sarebbe il Mancala).

Daniele Ferri

Giocatore di lungo corso. È l’unico ad aver partecipato – e sempre con buoni risultati – a tutte le edizioni del “Giocatore dell’Anno” (ah, che nostalgia!). Capace di sfidare chiunque a qualunque gioco, qui alle MSO ha sempre ottenuto ottimi risultati. Ora è anche orgogliosissimo autore, col suo amato VegeTables, pure presente qui a Londra.

Gert Mittring

Alle Mind Sports Olympiad non solo giochi, ma anche discipline mentali in senso lato. Una di queste è il “Calcolo mentale” e Gert Mittring ne è il profeta. Raga, io il calcolo mentale me lo mangio a colazione, ma qui siamo oltre… oltre i raggi che balenavano alle porte di Tannhäuser. Vi posterò un modulo delle gare, così vi divertite un po’… ahahahah.

Glenda Trew

Se nel mondo oggi si conosce la magnifica famiglia di giochi che va sotto i nomi di Oware/Mancala/Awele/Wari… il merito è anche suo e della sua Oware International Society. Instancabile divulgatrice e appassionata giocatrice.

Etan Ilfeld

È il principale organizzatore delle Mind Sports Olympiad. Background scientifico e imprenditore di tutto ciò che lo appassiona: giochi, libri, arte contemporanea, regia e altro. Ha inventato il “Diving chess”: la scacchiera è ancorata sul fondo della piscina e la tua mossa la fai in apnea.

Andres Kuusk & Co.

“Estonishing!”: non è un tipo, è un neologismo inglese che mi è venuto in mente, dato che nel 2014 il “Team Estonia” ha ottenuto dei risultati che potremmo definire “astonishing”. Andres Kuusk vince il Pentamind, Madli Mirne vince il Pentamind femminile, Martin Hobemagi vince il Pentamind juniores. Eccoli tutti e tre insieme, diciamo, venuti dal freddo…

Alain Dekker

Sudafricano trapiantato a Londra, molto competitivo in innumerevoli giochi, ma sempre disposto a sacrificare il rigore del torneo a una visione più “ludica” degli stessi tornei, che a suo dire devono sempre garantire la soddisfazione anche dei principianti e non solo dell’etile di assatanati Pentamind-hunters. Il lato buonista dell’agonismo.

David Pearce

Ha partecipato a tutte le 19 edizioni delle Mind Sports Olympiad ed è di gran lunga il giocatore che si è aggiudicato più medaglie, quasi 150 (centocinquanta!). Un vero collezionista, e oltre a medaglie di metalli vari ama raccogliere anche titoli mondiali: c’è un torneo valido per un Campionato del Mondo? Lui ci partecipa di sicuro e state sicuri che batterlo sarà ben difficile.

Joseph Kollar

Alle MSO è un’istituzione. Da parecchi anni arbitra moltissimi dei tornei, cercando sempre di privilegiare l’aspetto amichevole al rigore tecnico. Quando può partecipa sempre volentieri alle gare.

INTERVENTI

Tutte le news sui nostri interventi pubblici: articoli, conferenze, commenti, dichiarazioni, interviste…